9 Things You Should Never Do On Ab Day

If you want to show off a ripped six-pack, make sure you're not committing any of these ab-day crimes!

Crunching down on your abs may seem like a simple-enough movement. Of course, if it were that easy, everyone would have a six-pack. A lot can go wrong between those sets of crunches and your chiseled middle.

Many of those wrong turns are made in the kitchen, serving only to pad your belly instead of peeling away your belly fat. But plenty can go wrong during the course of your ab workout as well.

We've identified the top nine things you should never do on ab day. And before you type it, of course we realize that you don't need a dedicated "ab day." You could be making these mistakes if you train abs daily, twice a week, or however you do it.

Of course, skipping your ab workout altogether would be the biggest mistake you could make!

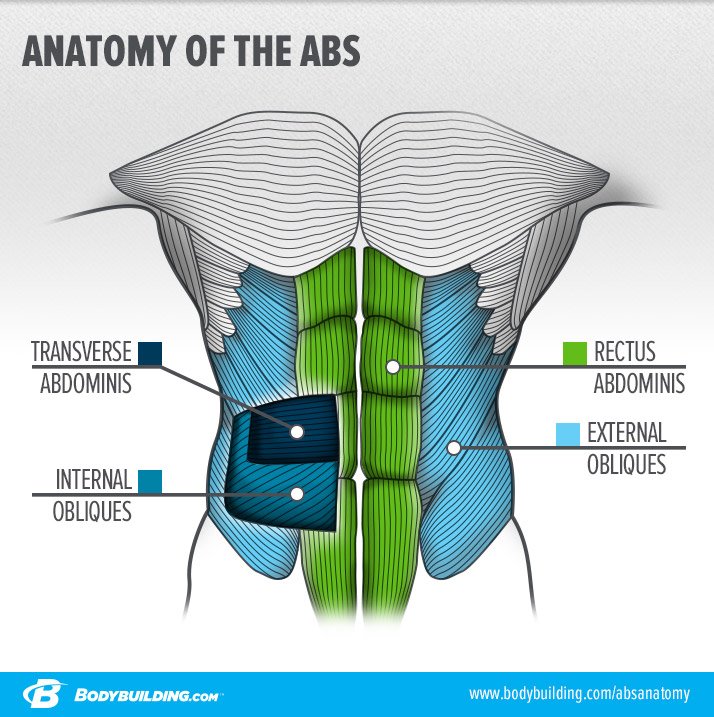

Never think of your abs as a single muscle

The six-pack may be what you covet, but there are several muscles you should be familiar with. The first is the rectus abdominis, a wide, thin sheath that runs between your sternum and pelvis. It has two main functions: forward flexion of the torso and raising the pelvis.

The obliques, both internal and external, run along both sides of the torso. The external oblique is the outermost abdominal muscle, with the fibers running diagonally from your lower ribs to the front area of the hipbone. It assists in trunk flexion. It also works during trunk rotation and lateral flexion of the torso.

Then there's the transverse abdominis, the deepest of the ab muscles. It runs beneath the rectus abdominis. This muscle is involved in movements that deal with abdominal compression, like when you suck in your gut doing planks. Since it's not visible, many programs don't train it—which is a mistake.

By understanding the various muscles of your midsection and how they work, you can better create a workout that addresses your strengths and weaknesses. In fact, while the rectus abdominis is a single muscle, you can emphasize one end—the upper or lower ab region—with changes in movement. (Notice we didn't say "isolate" a particular aspect of it.)

To focus primarily on the upper portion, stabilize your lower body as you curl your upper body down, reducing the distance between your rib cage and pelvis. A good example of an upper-ab move is the cable crunch, in which your lower body doesn't move. To better target the lower region, it's just the opposite: Your upper body is stabilized and you raise your legs up, which curls your pelvis up. A good example of this is the hanging leg raise.

Some ab movements allow shortening at both ends, such as a crunch in which your rib cage and pelvis are moving toward each other, which effectively targets both the lower and upper abs.

During oblique movements, you're twisting, rotating, or working in the lateral plane, such as when doing side bends.

Never fear added resistance

There are literally dozens of bodyweight ab exercises you can choose from. A big plus: You can do many of these at home without having to go to the gym, and they don't require any special equipment.

The downside? As you get stronger, you can do more reps or decrease the rest time between sets, but with bodyweight movements there's really no option to increase the load. That's why we prefer weighted ab movements. As you get stronger, it's easier to add another plate to the stack to keep your gains coming.

Although the abs contain a greater percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibers than other skeletal muscle groups, fast-twitch fibers make up almost half of your midsection musculature. Many bodyweight movements you can do for high reps don't effectively target these fast-twitch fibers. What's more, slow-twitch fibers that are better capable of endurance don't respond to a training stimulus by growing larger. Instead, they become more aerobically efficient.

Heavier sets for low-to-moderate reps are ideal for building up those fast-twitch fibers, the ones prone to growth. Using added resistance to train with as few as 8-12 reps will help build up the bricks constituting your six-pack. In that sense, training abs is a lot like how you target other muscle groups for growth.

Use cable and machine crunches, and tack easier bodyweight exercises on to the end of your workout to really incite the muscle burn.

Never grow comfortable with your ab routine

Falling into a comfort zone is your enemy when training abs—or any other body part. Besides adding weight to increase the overload on a target muscle, you can also increase the number of reps or decrease the rest intervals between sets.

Building in progression is just as important for ab training as for any other body part. As your body adapts to a training stimulus, you need to continue to increase the stress to continue making gains. That's the progressive part of progressive overload.

If your ab routine consistently includes exercises for 3 sets of 20 reps, and you seem to be doing the same work every ab-training session, it's time to up the ante and intentionally make your training harder. As you become stronger and do more reps with a given exercise, increase the amount of resistance. Always strive to improve on what you did before.

Never keep your back flat

All too many people mistakenly keep a flat back when doing cable and decline crunches and other movements. Maintaining a flat back is a carryover from when you learned proper exercise form for bent-over rows, deadlifts, squats, and bent-over lateral raises.

But consider this: When you isometrically contract your lower back to keep it flat, you cannot also actively contract your abdominals, which is the antagonist muscle to your lower back. Hence, that flat back prevents your abs from shortening.

When training abs, you need to unlearn what under other circumstances is a healthy habit. Maintaining (locking) a flat or slightly arched back in the lumbar region hinders abdominal development. Trainees who maintain a flat back end up bending at the hips, not the waist. Only when you bend at the waist are you able to fully crunch the rectus abdominis, causing it to shorten; at the same time, the lower-back musculature is being stretched as it rounds.

Think of your spine curling in a controlled manner on the concentric motion, and then uncurling on the eccentric, during ab exercises to better focus on working the muscle more directly.

Never rest between reps

If you're training with cables or machines, never allow the plates to "touch down" between reps. That's when the weight bottoms out against gravity, and all the force you've carefully taken to the end of the range of motion instantly dissipates—what's called the "stretch reflex." With the weight essentially resting on the stack, the tension on the muscle is eliminated and allows for an ever-so-brief moment of rest.

That's easy to see with machines, but it's less obvious on many ab exercises, especially bodyweight movements. With these exercises, you're often lying on your back; the movements typically require you to rise up and bring your shoulder blades off the mat. All too often, however, an individual comes completely back. This allows the next rep to begin from a resting position.

Keeping tension on the target muscle for the duration of the set requires you to know when you've extended the range of motion too far, building in multiple "rest" spots. In the fully stretched position, you still want to feel tension on the muscle, not be starting from any kind of resting position.

Never fly through your reps

An inexperienced trainer will often do a set with the intent of completing as many reps as possible—and then goes on to do them as fast as possible. But reaching a numerical target shouldn't be your goal in and of itself; instead, it should be on quality reps in which you fully fatigue your abs. Racing through your set invites momentum, which often means that work is being taken off the abs.

A quality rep entails starting each rep with tension on the muscle (see Tip 5). It takes the target muscle, most often one end or the other of the rectus abdominis, through a full range of motion. To ensure you're minimizing momentum, hold the top (peak-contracted) position for a count, and consciously squeeze your abs.

Switch your focus from quantity of reps to quality of reps. You may end up doing fewer reps in the end, but you'll make the muscle work harder, which is really what you want to be doing.

Never intentionally activate your hip flexors when training

This is one you've likely heard before, but let's explain exactly what it means. The hip flexors are a group of upper-thigh muscles that attach below the pelvis, whereas the rectus abdominis attaches above the pelvis. Many trainees mistakenly work the hip flexors thinking they're doing a lower-ab movement. But there's a difference.

Hang from a pull-up bar and keep your body straight. Now raise your legs about 60 degrees. Notice how your lower back is still flat—it hasn't started to round. That's an indication your lower abs aren't yet engaged; it's all hip flexors to this point because they're responsible for raising your legs (hip flexion).

Now continue raising your legs well past the point at which your thighs are parallel to the floor—as high as you can—and you'll see how your lower back starts to round as you pelvis curls up. That's an important distinction.

Just raising your legs doesn't ensure the lower abs are activated until you pass a point at which your lower back starts to round. Again, when your lower spine starts to curl, it's a sign that your abs are shortening.

Never pull on your neck

Bodyweight exercises have their place in ab training, especially toward the end of a workout or when training at home. Many are done with your hands placed behind your head, as a means of support. But all too often, trainers will pull on their head to aid the movement—which does nothing besides push their chin into their chest.

Pulling on your head doesn't work your abs, but it can disrupt your spinal alignment. During exercise, you want to maintain spinal alignment from the lumbar region to the cervical spine. Pulling on your head serves only to place your neck in a vulnerable position.

With bodyweight moves, the chance of damage is somewhat limited, but it's good to be aware of spinal position and what constitutes good body position. Let's just say it's a lesson you don't want to have to learn when you're doing shrugs with hundreds of pounds in your hands.

Never think you can crunch away a bad diet

Some people think that if they blow their diet—say by scarfing down chocolate cake for dessert—they can simply compensate by doing a bit more exercise, and that it'll magically be a wash. If only it were that simple.

Let's assume for a second that the cake totaled 500 calories—and those macros exceeded your daily goal. That means you'd have to do 500 calories' worth of exercise to ensure those extra calories don't become body fat. Crunches won't do it because abdominal contractions are small fries compared to working larger body parts that engage more total muscle mass. Hence a cardio activity, even a tame one like walking, is more suitable.

How long would you have to go to burn off that piece of cake? If you weigh 170 pounds, you'd have to walk on the treadmill for 125 minutes, assuming a calorie burn of four calories per minute. That's two hours for just one cheat dessert! And what if your diet requires more cleaning up than that?

I've never met a physique athlete who didn't agree that abs are made in the kitchen., and that you can't out-train a bad diet. Exercise alone isn't going to make your abs pop if they're hidden by a layer of body fat. Unless you're willing to invest hours on cardio machines, what you eat is the most critical factor in abdominal definition.