Strength First: Ditch The BOSU Ball For The Barbell

New to the gym? You don't have to start with a wacky stability exercise on the BOSU ball. Learn why building strength with a barbell should be your top priority!

During a recent visit to a local gym, I watched a trainer lead his visibly out-of-shape client through an incredibly difficult gauntlet of movements. First, she was on one foot, struggling to stay upright. Next, she was tottering on two feet atop a BOSU platform, and finally—you guessed it—she was standing on the BOSU on one foot. I actually overheard the client apologize three or four times, saying, "Sorry, I just can't keep my balance!"

Of course, this woman shouldn't have had to apologize—her trainer should have! But on one level, I understand why she didn't put up a fight. Let's face it: Stability-focused work like this is hard. It will make you struggle and sweat, particularly if you're not used to doing it. The client in question definitely wasn't bored—far from it. She probably felt like she was fighting for her life—and she no doubt felt she "got a workout."

But at the end of the hour, that was all she got. She wasn't any closer to making the sort of changes that would carry over to feeling and looking better—her likely reasons for going to the gym in the first place.

What this client really needed was more strength, more muscle, less fat, and a faster metabolism. But what she was getting was a recipe for another "three paid sessions and never to return" failure. She deserved better! Here's how she could have gotten it.

Is Strength Your Weakness?

In a recent social media post, Dr. Mike Israetel made a compelling point about the use of unstable training methods for MMA athletes. After pointing out that balance is mostly genetically determined (read: not trainable), he noted that the overwhelming majority of jiujitsu competitors do not have conspicuous levels of strength or muscle. Why? Because practicing their sport doesn't offer opportunities to place high tension on major muscle groups, since they are rarely in a stable position against a high level of resistance for any significant length of time.

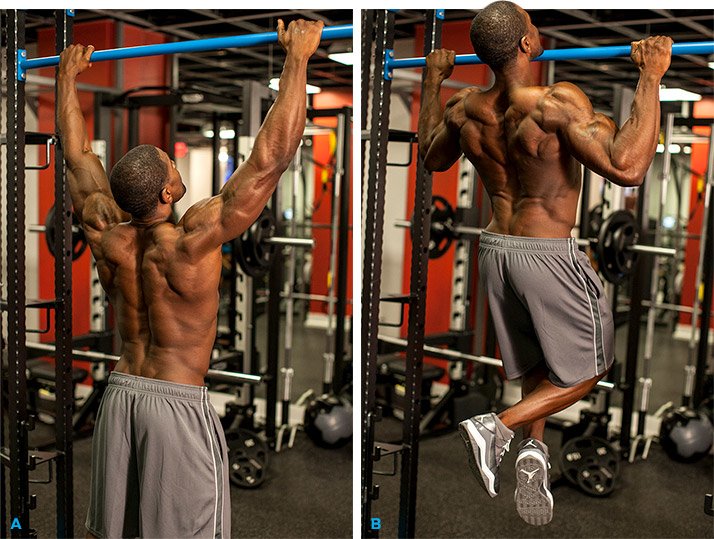

In other words, strength is often these athletes' weakness, not stability. Examples of this can be seen in various sports. NBA star Kevin Durant can score at will from any contorted position on the court, but he got plenty of flak back in 2007 when he couldn't manage a single bench press rep with 185 at the NBA combine. Top hockey prospect Sam Bennett is a demon on skates, but was ridiculed for not being able to do a pull-up last year at the NHL combine. Most of us probably know a highly talented runner, triathlete, or cyclist in more or less the same boat.

pull-up

Now, we could sit here all day and debate how much strength any type of athlete needs, but suffice it to say, those who need it have to build it the old fashioned way.

Traditional weight-training does offer opportunities to get stronger—unless of course, you attempt it in an unstable environment. The moment you take away stability, you also remove most of the benefit. Strength must be done right!

The Place for Correctives

Before I risk seeming dogmatic, let me be clear: I'm not saying that all exercises that use low weight, venture out of the sagittal plane, or prioritize stability are without merit—far from it. Proponents of the exercises I'm taking to task here will argue that, when used in the proper context, stabilization exercises offer great benefit, and I agree—the "proper context" being an injured client at a physical therapy office. Outside of that setting, not so much.

Likewise, measured doses of drills like kettlebell get-ups, stir-the-pots, and various single-leg squats can absolutely benefit people when applied in the right context and for the right reasons. My specific criticism centers on the almost exclusive use of such movements for people who are not physical therapy patients, and who would benefit far more from simply getting stronger and more muscular.

So how should they do it? It's no secret: Place large tension on major muscle groups. Do squats, rows, presses, and perhaps a few ancillary drills such as lunges, kettlebell swings and roll-outs.

If you're a trainee, the take-home message is to take control of your goals—don't trust your trainer to do it for you. If you're injured and in need of therapy, absolutely go and get it. But if you're not, it's OK to say, "I want to get stronger, leaner, and build muscle." Being frank about this and working toward your specific goals can do wonders, especially if you take meticulous notes along the way.

If you're a professional trainer, just remember that growth requires constant reevaluation of paradigms and practices. It also demands a willingness to admit when you're wrong. Take a hard look at your personal practice and your professional one. Keep an open mind, but don't forget about what has always worked.

Deadlift

Embrace the Boring

As a final observation, most of us under-appreciate the value of looking at historical examples of what works in various fields of human pursuit. When you look back at the biggest, strongest, leanest, and—dare I say—most "functional" athletes in history, you'll see that most of them relied primarily on the staple movements I've already discussed in this article. It's only recently that physical therapy exercises have leaked over to the gym, after all.

If you have a specific goal in mind, evaluate methods solely for their ability to produce those results—not for their popularity or their ability to temporarily relieve your boredom. If you can get excited about doing what other people think is boring, you can excel at anything!