Pro Bodybuilding Has Lost Its Way

The Olympia only reinforced criticism from Arnold Schwarzenegger of the sport he popularized. But while he implicates the judges for the sorry state of today's physiques, a closer look reveals there is plenty of blame to go around.

On March 8, 2015, less than 24 hours after joyfully congratulating the winner of the Arnold Classic in Columbus, Ohio, Arnold Schwarzenegger dropped a bombshell on the fans and reporters who had assembled for his annual Sunday morning seminar. He forcefully blasted the state of elite competitive bodybuilding, casting blame on IFBB head judge Jim Manion and other officials for "choosing the guy with the biggest neck and the biggest muscles" and other "bottle-shaped" bodies instead of a more aesthetically pleasing physique epitomized by the legendary Steve Reeves. It was a stinging rebuke that echoed through chat rooms, web boards, and gyms for weeks afterward.

Schwarzenegger is that rare public figure who has gone from subculture to global celebrity but still never strays far from his insular primordial roots. This is a man who once ran the world's eighth largest economy as governor of California, was a global box-office king, and here he is, ruminating on the aesthetics of a sport barely classified as such, whose participants are described as athletes, but who are more likely found in the culture pages than the sports pages. He can't be written off as an out-of-touch has-been, complaining about "those kids today" from his rocking chair.

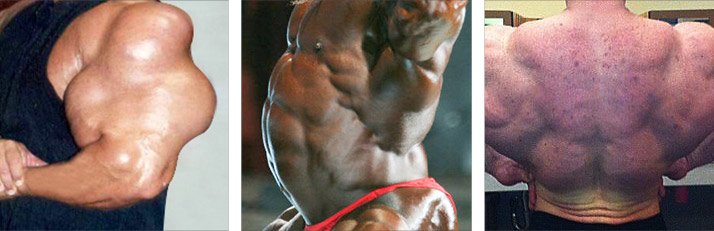

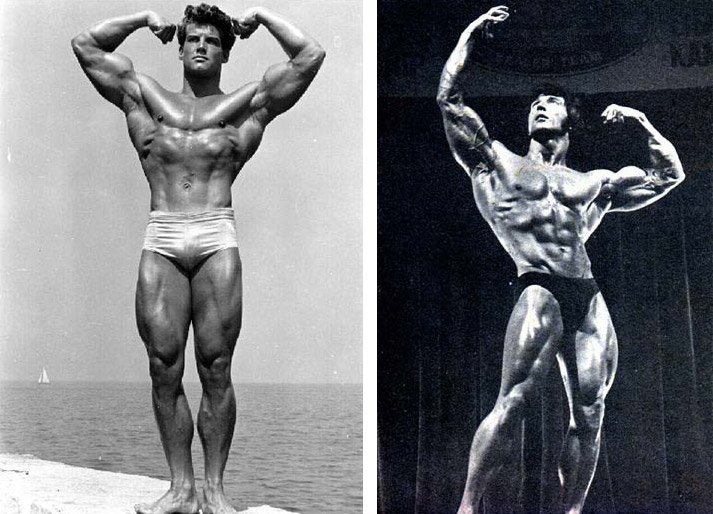

Many agree with him. Veteran observers of bodybuilding know what he was talking about: distended guts, Synthol bulges, acne scars, hypodermic abscesses, and Michelin Man levels of disproportionate body parts. Sometimes, the stage of a bodybuilding show looks like a group of household appliances with heads. What these bodybuilders lack can be found in the physiques of Arnold's competitive heyday during the '70s, known as the Golden Age of bodybuilding.

Not a year goes by that the contoured body of vintage Frank Zane isn't hoisted up on a pedestal and declared the ideal masculine aesthetic, the structure that all bodybuilders should strive toward. Images of a '70s-era Schwarzenegger on magazine covers still sell better than contemporary stars. This was the look that made the sport, that created an entire industry.

The Golden Age, Tarnished

While it's often agreed that we should return to the aesthetics of the Golden Age, there's considerable disagreement over how the sport has arrived in the state it is today. Sometimes it's blamed on the so-called gurus, many of whom are nothing more than drug advisors/couriers, administering (sometimes mislabeled) black-market prescriptions without medical degrees.

But this state of affairs preceded the gurus. In the mid-'90s, an editor at Flex magazine once asked a top bodybuilder for a copy of his workout schedule. This particular competitor, known for his educated wit, gave the editor his drug schedule as a joke. It was a sardonic statement about the imperative of pharmaceutical assistance to success in elite bodybuilding. The phrase, "It's funny because it's true," comes to mind. Only now it doesn't seem so funny.

Twenty years later, the body count of top pro and amateur bodybuilders grows by the year. I personally knew many of these men who have passed—Don Youngblood, Art Atwood, Mat DuVal, Greg Kovacs, Luke Wood—but the one that hit me the hardest was Mike Matarazzo, the Boston-born happy warrior who died waiting for a heart transplant last year. Before he left us, he warned others about following his path.

Matarazzo's death made me contend with another responsible party to this mournful list of the dead: myself and my media brethren.

We saw this coming. We watched top pros go on dialysis, walked with lumbering hulks who ran out of breath after climbing a single flight of stairs. I once saw a competitor go into insulin shock backstage at a contest before medics stabilized him and whisked him away in an ambulance.

Judgment Days

Like Arnold, you can blame the judges, but even they have limited influence. I've been at shows where judges marked down misshapen drug monsters, only to be met with howling scorn from the audience. In a subjective sport that lacks rigid criteria for scoring, crowd reactions can have an overwhelming influence on the official scorers. This is true on the women's side as well as the men's. In 1992, Britain's Paula Bircumshaw entered the 1992 Ms. International contest in massive (for its day) shape, but was marked down in favor of her streamlined competitors. She didn't make the final top-six posedown.

Backstage in her street clothes, she heard the crowd chanting her name. She answered their calls and returned to the stage, attired in her sweats, and mockingly gestured at the smaller women who had eclipsed her in the placings. The audience screamed with approval.

Bircumshaw was banned from competing for six months, but she became a folk hero to the grass roots. The judges got the message. And so did the bodybuilding press. In the '90s, before the Internet, magazines like Flex, Muscle & Fitness, MuscleMag, and Muscular Development ruled the discourse. Paula was good copy, and proof of the primacy of the spectacle. As a result, the women's sport became more welcoming to the bigger dimensions, eventually leading to complaints of masculinized women overloaded on androgens, unpalatable to those within the sport and a walking PR disaster outside of it.

Gradually, women's bodybuilding on the pro level is disappearing, giving way to the less-muscular standards of the women's physique division. The Ms. International, the show Bircumshaw's mass had so disrupted, no longer exists, replaced by the Physique International. (It should be noted that Bircumshaw, a very pleasant woman, was no drug monster. By today's standard, she could almost fit into the physique division.)

Disposable Commodities

This seems to be the modus operandi of the IFBB: create a new division, develop the preferred standard, then phase out the old division. A similar process may be in place with the creation of the men's physique division, which displays a more streamlined, more attainable muscular body. Then this summer, in what seemed like a direct response to Schwarzenegger, Manion announced the creation of a classic physique division.

Fans and sports media demand the spectacle, then express outrage when the corpses pile up. World Wrestling Entertainment is famous for its roster of wrestlers who died young, most often from accidental overdoses, suicides, and heart attacks. The National Football League, the nation's top spectator sport, has similar issues with concussion-related early deaths. These calamities have little effect, if any, on the popularity of these athletic entertainments.

What all of these sports have in common, more than performance-enhancing drugs, is a system that treats professional athletes less as human beings than as disposable commodities. Some may argue that's the tradeoff: You get the big check and stardom, and you take the risks.

Maybe that's true. But I can't stop thinking about Mike Matarazzo, a husband, a father, a friend, and a spark of life who should still be laughing and joking with the rest of us.

By the way, the bodybuilder who had given the Flex writer his drug schedule as a gag? It was Nasser El Sonbaty. He died at 47 years of age from heart and kidney failure.