I like to think of myself as a powerful, modern Highland warrior, or maybe a Viking. Had I been born 1,100 years ago I would have leapt first off the longboat to battle hundreds of enemies with a giant axe, or so the fantasy goes. But, it didn't take strength coach Matt Wattles long to put a pin in that balloon. All he had to do was ask me to raise my toes all the way up to his hands, and in an instant, I felt like a senior citizen with a hip replacement. That movement was hard.

Unfortunately hip mobility issues like these are some of the most common problems I see in the weightlifting population. However, the issues manifest differently in different people. In some, it's a basic inability to descend below parallel—or anywhere near it—in squat variations. In others, it can contribute directly to debilitating lower back pain, even in people who spend hours every week strengthening their backs.

The hip flexors in particular can be troublesome little cusses. These muscles are crucially tied to the functionality of everyone from elite athletes to senior citizens, but working them can make anyone feel silly. After all, you never see videos of Ronnie Coleman walking with his arms extended in front of him like a zombie, attempting to raise his toes up to his hands.

It's time to swallow your pride and get serious about this neglected area of your body. Use my three-pronged attack, and your weak hip flexors will simply have no choice but to get stronger and healthier.

Meet The Hip Flexors

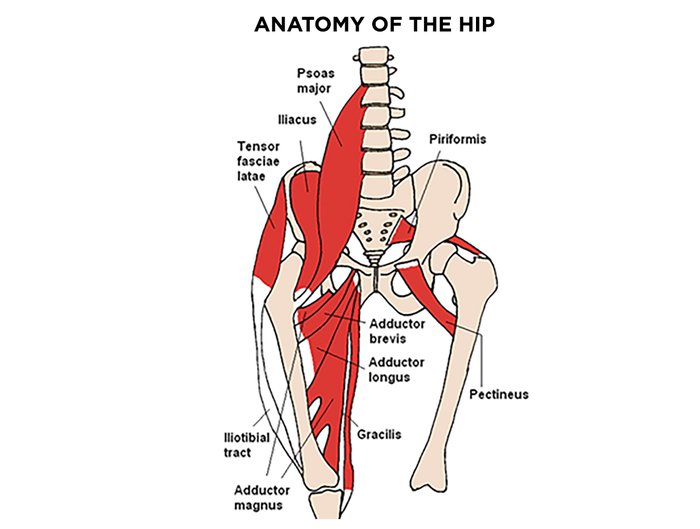

The hip flexors are a group of five muscles that connect the femur (or thigh bone) to the pelvis. They move in one of two ways. When the pelvis is stationary, a contraction of the hip flexors will draw the femur upward—think the classic "goose step." Conversely, if the femur is stationary, a contraction of the hip flexors will tilt the pelvis forward and the butt back—think of the pull-back portion of Garth's many hip thrusts beginning at about 40 seconds in ... foxy lady!

Last month, I talked about the unique complexity of the shoulder, and how a problem there can produce effects throughout the upper body. Well, the hips are just as complicated, and pelvic dysfunction can be just as far-reaching. Your erectors, glutes, hamstrings, abdominals, quadriceps, hip flexors, and more all interact at this junction, and a problem with any one of them can lead to debilitating immobility and weakness in lifting and in life.

You may have been told that the answer is to undergo a barrage of awkward hip flexor stretches as often as possible. In truth, that's only part of the solution. As with the shoulder, you need to smash, stretch, and strengthen your hip flexors in order to improve them.

1. Come Unglued

The first step in building better hip flexors is to spend some painful minutes ungluing tissues that have been frozen from years of sitting at a desk. I recommend rolling, aka "self myofascial release."

You can roll on just about anything. I've used several different types of foam rollers, a Rumble Roller, lacrosse balls, PVC pipe, a number of weird stick-shaped things. I've also been getting great results using the Body Wrench, an awesome device that is basically a combination of all of the above. I have found that different materials are suitable for different areas on different bodies, so feel free to experiment and find what works best for you.

Keep adjusting your position until you find a hot spot, and then hold that position for at least 30 seconds.

To work these tissues, start by locating your iliac crest. Sounds like a rare bird species, but it's the top bony part of your hip that sticks out by your beltline. If you're using a lacrosse ball, simply move into a plank position on the ground and lay on the ball so that it presses into your hip just below the crest. Move side-to-side slowly, so the ball moves back and forth laterally several inches at a time.

Keep adjusting your position until you find a hot spot ("A what? I don't know what you're ... Oh! My God! There one is!"), and then hold that position for at least 30 seconds. Your first impulse will be to tense up when you feel tenderness, but it's important that you relax and continue to move around the area. Keep it up, and don't hurry. The more slowly and more often you can do this, the better.

2. Get On The Couch

Now that we smoothed out that old tissue and dislodged a few fossilized nasties, let's see what we can do about improving extensibility. The couch stretch is one of the most effective movements you can do for opening up your hip to the end range of motion. Adopt a kneeling position in front of something that you can use to hold your foot up (i.e., a couch). Your back knee should be completely flexed, meaning your heel is as close as possible to your butt.

It's easy to compensate in this position by hyperextending your lower back, but it's crucial that you don't. Instead, I want you to focus on squeezing your glutes and hamstrings, which will push your hips forward into a full-on "schwing." If your right foot is back, you should feel an intense stretch on the right front side of your hip. Hold it for a long time, like a minute or two, and then switch sides.

Like rolling, this is a movement that deserves to be done as often as you can tolerate. Physical therapist and coach Kelly Starrett has written that you should do it for two minutes on each side every half hour. That may be tough to manage, but the point is this: Frequent, long-duration stretches are the only stretches that will have any significant effect on your tissue length and mobility. If you want to improve, you have to commit.

3. Build Flexible Flexors

When I first began training, I assumed that because I had short, tight hip flexors, they must be strong. Wrong! Because we spend so much of our lives sitting—a position in which the hip flexors are passively contracted—most people's flexors are both short and weak.

The psoas, our primary hip flexor, is usually the weakest of the five flexors, and the other four hip flexors have to work more as a result. To test if this is the case for you, lift one knee well above 90 degrees and hold it there, ensuring that you do not compensate by moving your pelvis or leaning forward. If holding this for more than a few seconds is painful or impossible for you, your psoas suck. You are going to have serious trouble squatting to parallel or lower if these muscles can't do their job properly.

One way to strengthen the psoas is by performing the type of toe-lifting movements I mentioned at the start of the article. However, in this case I prefer to rely on closed-chain movements, where the hands are fixed and can't move. This small change makes it harder to cheat or compensate, allowing you to focus squarely on the movement.

My exercise of choice here is floor-slide mountain climbers. You will need some furniture moving pads, Valslides, or something similar that will slide smoothly on your floor. Paper plates even work well in a pinch. Put your feet on the sliders and move into a push-up position. To perform the movement, simply pull one knee at a time up toward your chest, going as high as you can while keeping your foot on the slider. You can alternate legs with each rep or do sets of one leg at a time. Don't expect it to be easy.

Floor Slides

Your hips may not lie, but they can really sidetrack your training if they fall out of whack. Implement this three-part plan, and your hips will be more effective in the gym and less prone to injury moving forward!